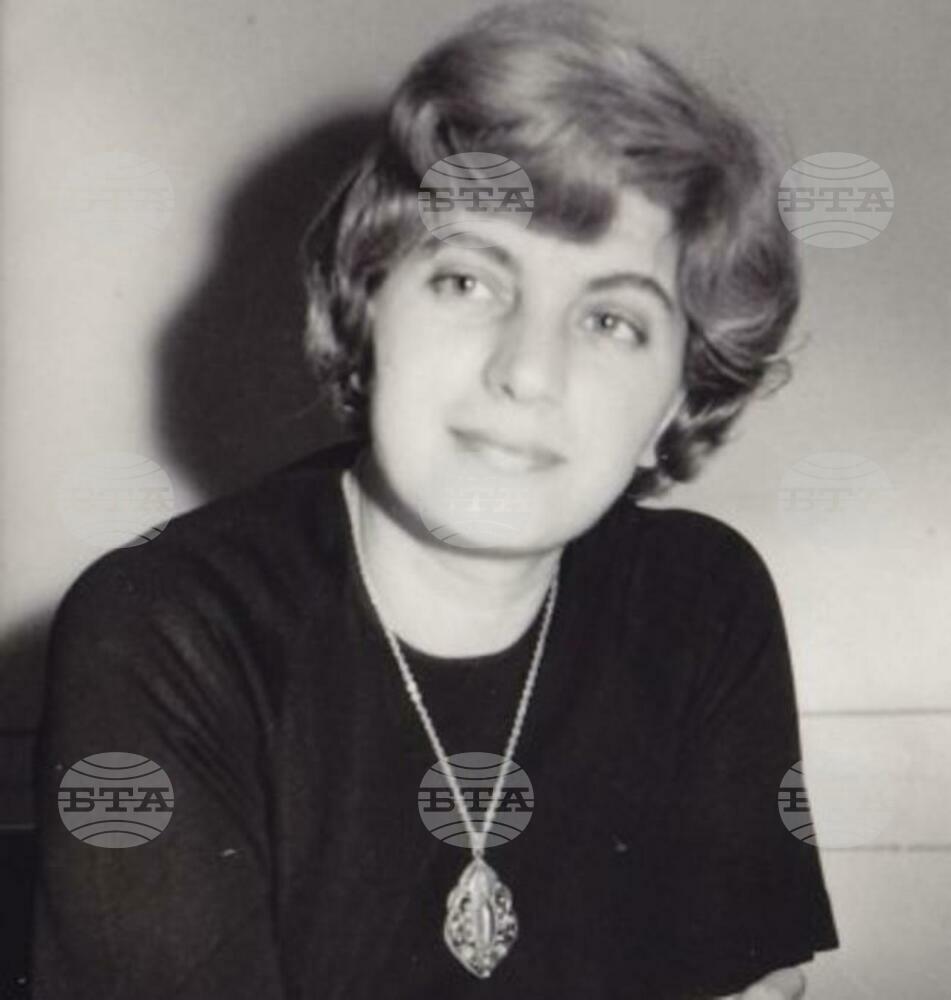

site.btaBirth Centenary of Blaga Dimitrova, Dissident Poetess and Reluctant Politician

The birth centenary of Blaga Dimitrova (1922-2003) this January gave Bulgaria an occasion to remember one of the most remarkable intellectuals in its recent history.

Blaga Dimitrova was born in Byala Slatina (Northwestern Bulgaria) on January 2, 1922 to the family of a lawyer and a teacher. She went to secondary school in Sofia, taking classes in ancient Greek and Latin, and graduated in Slav Philology from the St Kliment Ohridski University of Sofia in 1945. She did postgraduate research at Leningrad University and at the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute in Moscow. She joined the Bulgarian Writers’ Union in 1946. Dimitrova worked as an editor at the literary monthly Septemvri (1950-1958), at the Bulgarski Pisatel Publishing House (1962), and at the Narodna Kultura Publishing House (1963-1982).

Versatile Talent

Blaga Dimitrova was a prolific author. Publication of her 22-volume Collected Works has been in progress since 2003, with 11 volumes released so far. She wrote 27 poetry books, eight novels, four plays, essays, travelogues and non-fiction (memoirs, biographies and literary criticism). Artistic brilliance and philosophical sophistication distinguish her writings.

Dimitrova’s vintage poetry addresses issues that appeal to every individual regardless of age, gender and occupation: life and death, love and friendship, motherhood, nature, truth and the power of the word, as well as all topical public concerns: freedom, responsibility, community, the place of women and care of others, says her aide Maria Petkova. This explains why 13 years after her death three of her novels (Journey to Oneself, Detour and Avalanche) still ranked second among the Top 50 best-selling Bulgarian books. “Seldom has a woman’s writing been at once more cerebral and more sensual,” Julia Kristeva wrote, commenting on her art. “Blaga Dimitrova can turn thought into poetry, meditation into rhythm and flavor, colors into ideas, judgment into fragrance, vision into ethical statement”. For his part, John Updike appreciated the poetess’s “breathless, oblique, and resolutely personal voice”.

Works of hers have been translated into over 20 languages. Her first collection of verse in English, Because the Sea Is Black, came out in the US in 1989. Several of her books have been filmed, including Avalanche and Detour.

Even as a secondary-school pupil, Dimitrova tried her hand at translation from ancient Greek and Latin (Homer’s Iliad, Ovid’s Metamorphoses). She also studied German and French. As a student, she translated Adam Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz (for which she won an award of the Polish P.E.N. Club in 1977). Her translations of Swedish poetry earned her an Artur Lundkvist Award (1984). Her other honours include a Gottfried von Herder Prize for poetry (1992), the French Ordre national du Mérite (1993), and the Bulgarian Order of the Balkan Range, First Class (2002).

Dimitrova took piano lessons from an early age. For her, playing the piano was as essential as writing poetry. “Music and poetry remain amalgamated into a single art,” she said.

Dissident and Public Activist

Blaga Dimitrova became interested in public life and politics when very young. Before the communist takeover in 1944 she was member of the then outlawed left-wing Workers Youth League (RMS). Curiously, though, she never joined the Communist Party despite numerous invitations to do so. She did write some poems extolling Communist leader Georgi Dimitrov and the proletariat, which her spiteful opponents unearthed when she ran for vice president in 1992. Increasingly disillusioned with the human rights policies and practices of the regime, Dimitrova became its outspoken critic. That cost her her job on several occasions. At a workers’ rally, she was symbolically “sentenced to death”, and a Writers’ Union member said that she should be “summarily shot in the square,” her Danish translator Helle Dalgaard recalls. Dimitrova’s novel Face, published in a curtailed and censored version in 1981, was nevertheless suppressed as it infuriated the top crust. Communist dictator Todor Zhivkov ordered the author of that book to be left “to subsist on bread and water”. She was not allowed to publish anything for two years. Zhivkov himself was ridiculed in her play The Bogomil Woman (1974), which did not see the light of day before the fall of communism in 1989, just as the unexpurgated version of Face.

The poetess shared in the formation of the Literary Artistic Circle 39 in 1987. She was among the founding members of the Club for Support of Glasnost and Perestroika in November 1988 and, before that, of the Public Committee for Environmental Protection of Rousse, set up in March 1988 to protest against air pollution of the city from a Romanian plant across the Danube.

In an essay entitled “The Name” (July 1989), she fearlessly opposed the forced name-changing of ethnic Turks by the totalitarian regime in the second half of the 1980s as “a barbarous encroachment” at a time when quite a few intellectuals toed the party line.

She was one of 12 leading Bulgarian dissidents invited to a famous breakfast with visiting President François Mitterrand at the French Ambassador’s Residence in Sofia on January 19, 1989. As a guest of honour, she was seated on the host’s right.

As communist rule collapsed in late 1989, Dimitrova, albeit euphoric at the newfound freedom, felt “crucified,” as she put it, between politics and poetry. In November, she addressed thousands of people at an anti-communist rally in central Sofia. In 1991 the poetess supported a hunger strike declared by 39 opposition members of the Communist-dominated Grand National Assembly in protest against the adoption of the new Constitution. She went on record as saying: “May the hand wither that will sign this Constitution.”

In October 1991 she won a seat in Parliament as a candidate of the right-wing Union of Democratic Forces (UDF). On January 19, 1992 she became Vice President of the Republic as the running mate of UDF candidate Zhelyu Zhelev, the first President of Bulgaria to be elected by popular vote. Ironically, Dimitrova had to pledge allegiance to the very same Constitution she had berated.

Just 18 months later, she set a precedent in Europe’s democratic history when she resigned her office on July 11, 1993, outraged by the criticism that Zhelev (her close friend for 12 years) had levelled at the UDF during an outdoor news conference dubbed “the Boyana Meadows”. She finally withdrew from politics in 1999, disgusted with “the unleashed demons of greed, spite and hate”. The guiding principle of her brief political career was “Not love of power but the power of love.”

Personal Life and Personality

Dimitrova’s schoolmate, actress Stoyanka Mutafova, remembers her as “amorous and always drawn to something or somebody”. There are numerous stories about the poetess’s romantic involvements with assorted celebrities: Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet (whom she accompanied on a tour of Bulgaria in 1951), writer Bogomil Raynov, university lecturer Petar Dinekov...

Her acquaintance with John Updike during a visit to Bulgaria in late November 1964 supposedly inspired the American author to write his award-winning short story “The Bulgarian Poetess” (1965). In the story, the protagonist, Henry Bech, is infatuated with Vera Glavanakova (a character possibly based on Dimitrova), describing her as “needing nothing, being complete, poised, satisfied, achieved.” Bech was “aroused and curious” when the Bulgarian playwright who accompanied him said: “She lives to write. I do not think it is healthy.” When they met again for one last “enchanted hour”, she was “slightly breathless and fussed, but exuding, again, that impalpable warmth of intelligence and virtue.” Bech found “an intense conjunction of good looks and brains” in Glavanakova.

For all that, the true love of her life and her closest soul mate was literary critic Yordan Vassilev (1935-2017). Having met at the funeral of a young critic who had committed suicide, they married on December 26, 1967.

A year earlier, in November 1966, Dimitrova took a six-year-old Vietnamese girl, Hoàng Thu Hà, into foster care. The poetess had met the toddler during one of her five visits to war-torn Vietnam and had returned six months later to locate her.

Dimitrova and Vassilev did not have children of their own.

Blaga Dimitrova battled with cancer in the 1970s and suffered a brain stroke by the end of 2002. Four months later, after a second stroke, she passed away on May 2, 2003, aged 81.

Bulgarian-born French philosopher Tzvetan Todorov referred to her as “a servant of truth and a master of words”. Her long-time friend and biographer, Prof. Elena Mihaylovska, says she was invariably engrossed, fully focused on her plans, pursuits or current work and, at the same time, attentive and generous to all. Eminent poetess Amelia Licheva remembers that, being an ardent cat person, Dimitrova always autographed her books adding a drawing of a cat to her signature. Career diplomat Stefan Tafrov describes her as spontaneous and cordial, possessing the gift of making her friends feel precious and interesting. According to Maria Petkova, the poetess was at the same time vulnerable and strong, gentle and bold, wise and very young in spirit, experienced and a perpetual seeker, eager to share in the sufferings and joys of the whole world.

/NF/

news.modal.header

news.modal.text