site.btaGeo Milev: The Prophet of Modernity

Poet Geo Milev was born 130 years ago Wednesday. A poet, translator, and journalist, he was best known for his epic poem Septemvri (September). His efforts in linking the local cultural context with the European one make of him a phenomenon of XX century Bulgarian culture.

Georgi Milev Kasabov, known as Geo Milev, was born in Radne Mahle (now Radnevo), Southeastern Bulgaria. His parents were school teachers. When the family moved to Stara Zagora in 1897, his father opened a bookstore and started a publishing business. Geo attended the town's high school and in 1911 went to study at the Sofia University Faculty of Philology. From 1912 he continued his education at the Leipzig University Faculty of Philosophy. In 1914, several days after the outbreak of World War I, he traveled from Leipzig to London, and during the return trip to Germany he was detained for eleven days in Hamburg on suspicion of being an English spy. He was released several days later and returned to Leipzig, where he worked on his university thesis on Richard Dehmel. In August 1915 he returned to Bulgaria without having earned a degree.

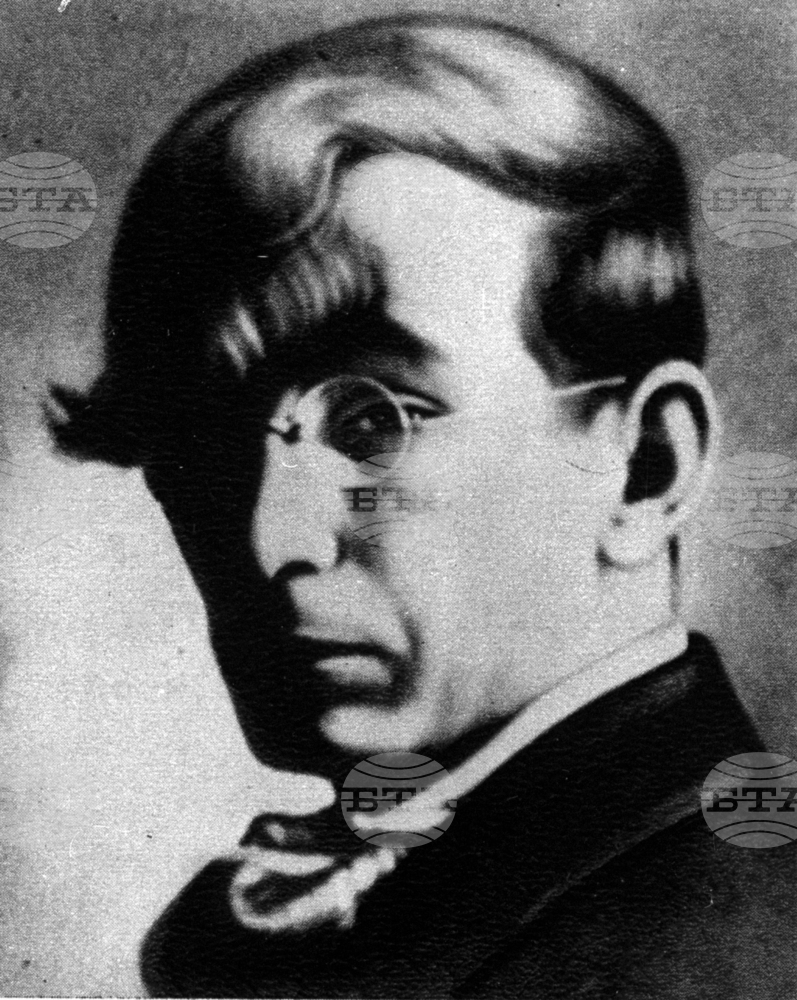

He saw action in World War I. On April 29, 1917, he sustained a horrible wound in the face and lost his right eye. His signature curtain bangs only partially covered the glass eye.

While recuperating in Berlin (where he underwent fifteen surgeries), he was already contributing to the magazine Die Aktion. Having already been exposed to Expressionism and Symbolism and knowledgeable of modern trends in European art, back in Bulgaria he launched started to edit the Bulgarian modernist magazine Vezni (Scales), in Sofia. He contributed to the publication as a translator, theatre reviewer, and director. His artistic interests were multifarious and included literary criticism, theatre, and graphic art (he himself being a talented painter).

On May 15, 1925, in the course of government reprisals following the St Nedelya Church bombing, Geo Milev, who leaned towards anarchism, was taken to a police station for "questioning" but never returned. It was only 30 years later that details of his death became public. Milev had been strangled with wire and then buried in a mass grave near Sofia. His remains were identified by the glass eye he was wearing.

The translator

Geo Milev was amazingly prolific as translator. He translated into Bulgarian works by over 200 authors. Also, he translated six Bulgarian writers into two foreign languages. Among the authors he translated are Andrey Bely, Valery Bryusov, Mayakovsky, Émile Verhaeren, Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine, Friedrich Nietzsche, Richard Dehmel, Alfred de Musset, Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud, Jean Moreas, Jules Romains, Anna de Noailles, Blaise Cendrars, Charles van Lerberghe, Maurice Maeterlinck… True, many translations were done for the purpose of compiling anthologies but, still, the scope of his interest remains unique for the Bulgarian cultural context. In less than a decade, he managed to create, parallel to his own poetry, a cultural space of translations from several languages. He translated Dante, Pushkin, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and was the first to translate Walt Whitman in Bulgarian…

Geo Milev was not a "translation machine", as the quantity of authors could easily suggest. His taste was visible and distinct, but terms like Symbolism, Modernism and Expressionism were too limited as references to his preferences. He was well versed into classic literature, mythology and aesthetics (clearly demonstrated in his best-known poem Septemvri), he possessed scholarly knowledge and ability to compare with established models. But he obviously preferred artistic innovation and experiments with form and content - and, above all, he preferred deep emotional involvement regardless of age, language or country.

Apart from all this, he produced articles on various issues and compiled a German-Bulgarian Dictionary.

But Geo Milev was above all a poet. And this could be felt in the remarkable sense of rhythm. The vocabulary, word precision and rhymes used in translations made a century ago certainly leave much to be desired. The rhythm remains characteristic of a poetic work, a personal footprint of the author. To be able to feel and render the rhythm into another language is a true art indeed.

To quote poet and translator Petar Velchev: "Translation of poetry is a complex, highly responsible art, requiring both talent and erudition, an art which performs important functions in the life of any nation. It is at the same time enlightenment, a vehicle of aesthetic education, an act of civic sympathy, an act of creation in the proper sense of the word, and a factor accelerating development of the verse of perceptive literature. Geo Milev's translation work brilliantly combines all these functions, and this makes it one of the most remarkable phenomena of 20th century Bulgarian culture."

/NF, LG/

news.modal.header

news.modal.text