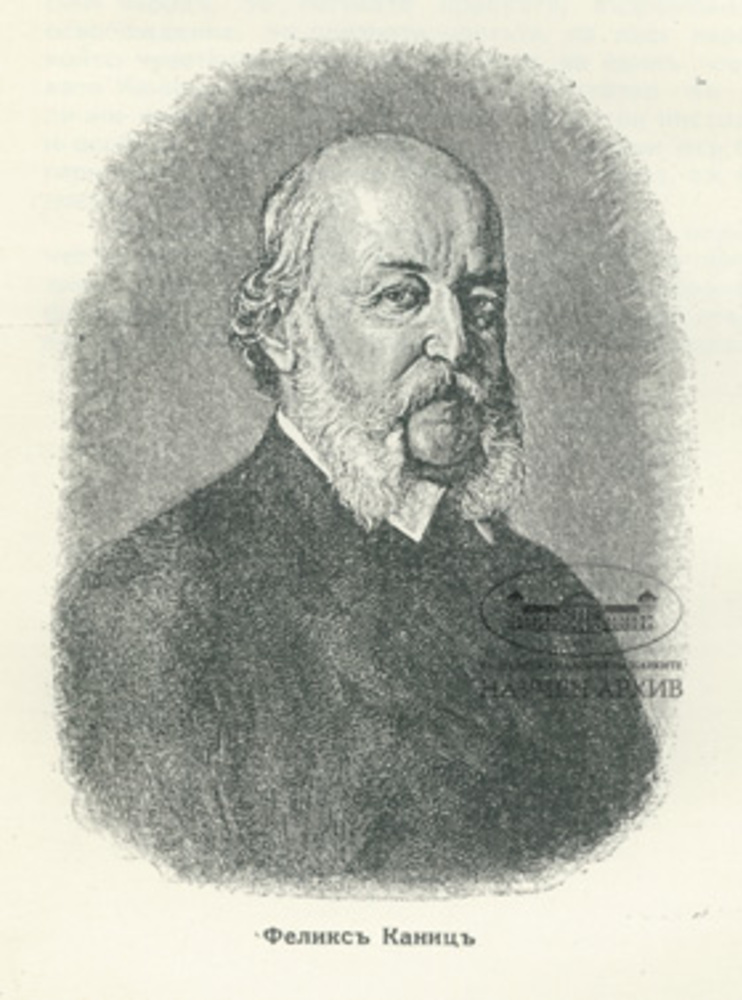

site.btaFelix Kanitz, the "Columbus of the Balkans"

Felix Philipp Kanitz (2 August 1829 - 8 January 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian traveller and ethnographer, whose travels earned him the flattering nickname "Columbus of the Balkans".

/RY/

news.modal.header

news.modal.text