site.bta80 Years since Bulgaria’s “Bloody Thursday”

Since 2011, by government decision February 1 has been marked in Bulgaria as a Day of Gratitude and Homage to the Victims of the Communist Regime. The largest single spate of executions in Bulgarian history was carried out on this date 80 years ago.

On the night of February 1 to 2, 1945, just hours after hearing their death sentences, 100 men were loaded in the back of six trucks and taken to the northern perimeter of Sofia’s Central Cemetery. An eyewitness remembers that they were shot there on the rim of an aerial bomb crater, at first one by one by a single bullet to the back of the head. Then, as the dawn approached, the procedure continued in batches of twenty by automatic fire. One of the condemned - a top surgeon, was left for last so as to pronounce the others dead. The common grave was filled with truckloads of cinders, and guards were posted to keep mourners away. The site was later turned into a waste dump.

The people who were executed on what came to be known as “Bloody Thursday” were part of the country’s political top brass that had been ousted by a coup on September 9, 1944: the three former regents of the underage King Simeon II (Prince Kiril of Preslav, Prof. Bogan Filov and General Nikola Mihov), ex-prime ministers Dobri Bozhilov and Ivan Bagryanov, 20 ministers of the five wartime cabinets, 67 members of the last Parliament before the communist takeover, and eight royal advisers.

The Court

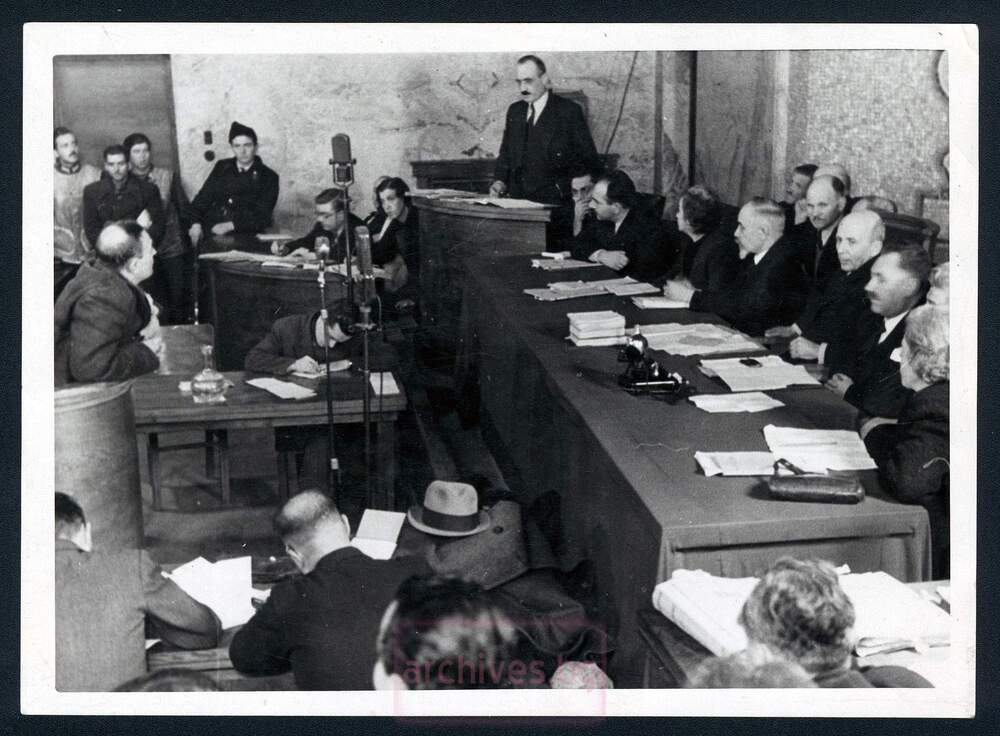

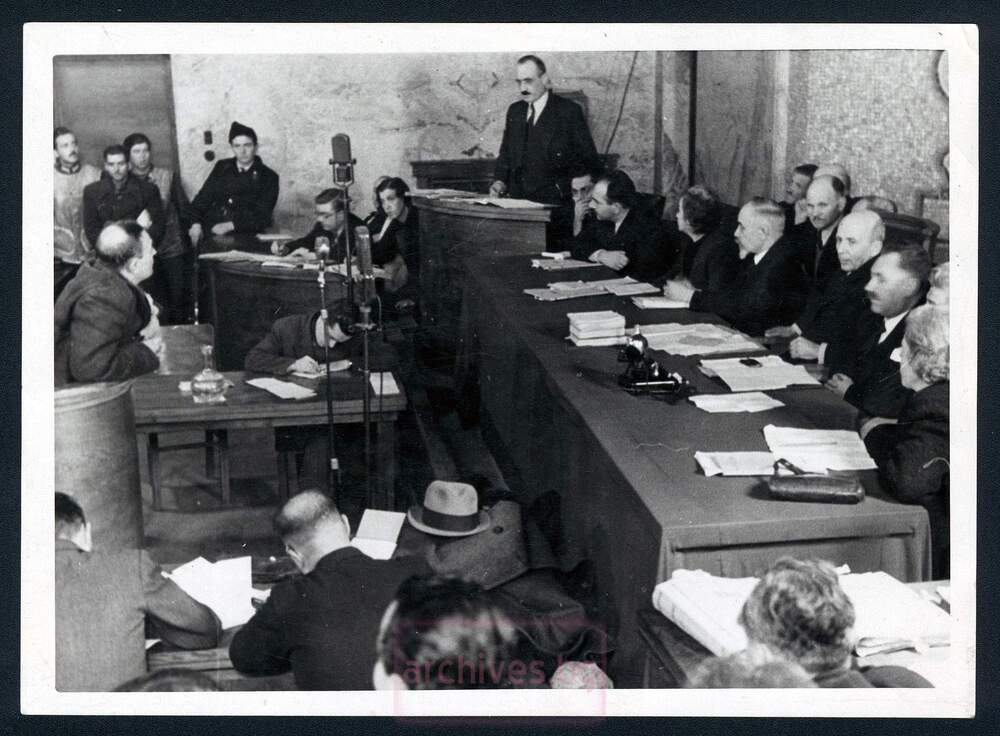

They were set to die under a sentence delivered by the First and Second Supreme Panels of the “People’s Court”, instituted by a Statutory Ordinance adopted by the Communist-led Fatherland Front government on September 30, 1944 and effective as gazetted on October 6, 1944.

This extraordinary criminal tribunal was supposed to deal with “the culprits for the embroilment of Bulgaria in the world war against the Allied nations and for the atrocities related to the said war”. The court was also competent to try, convict and sentence deceased persons, even if they had died before being charged. The judgments were unappealable and were to be implemented immediately.

The penal sanctions varied from death to life imprisonment in solitary confinement to custodial measures for a set term, plus a fine of up to 5 million leva, deprivation of civil and political rights, and forfeiture of all or part of the convicted person’s assets.

The Interior Ministry reported that 28,630 people implicated as culprits had been arrested by mid-November 1944. Of these, over 11,000 were charged and appeared before 13 supreme, 68 regional and 125 ordinary “People’s Court” panels.

The trials began in Sofia on December 20, 1944 and continued countrywide until May 1, 1945.

The Sentences

Reports by the Chief People’s Prosecutor Georgi Petrov and Justice Minister Mincho Neychev and later archive data cite diverging breakdowns on the outcome of the “People’s Court” trials for the period between December 22, 1944 and March 31, 1945.

Defendants: 10,919, 10,907, 10,920 or 11,122; cases: 131, 133, 135 or 145; total sentences: 9,550 or 10,897; death: 2,618, 2680 or 2,730 (of which 1,045 or 1,576 carried out, and including 202 death sentences of deceased persons); life: 1,226, 1,305, 1,920 or 1,921; 20 years’ imprisonment: 8 or 19; shorter prison terms: 4,304, 4,930 or 5,374; acquittals: 1,485 or 1,516.

The actual death toll exceeded 1,576. A large number of the accused were killed by the Communist combat groups and militsiya officers sent to detain them. When called out in the courtroom, they were listed “at large”. Some 200 of the condemned people had already been executed extra-judicially even before or during the proceedings. Even though the death sentences of not fewer than 41 persons were commuted to life imprisonment, the capital punishment of some of them nevertheless went ahead later on. A large part of those who were given prison terms were beaten and tortured to death immediately after the sentencing.

Raison d’être

While the proclaimed task of the “People’s Court” was to try German collaborators and wartime criminals, it was immediately turned into an instrument of political vengeance and personal vendettas. Apologists argue that this was “necessary and inevitable wartime justice”. For public consumption, the count of the old regime’s victims was grossly exaggerated. Vasil Kolarov (the number two in the Communist party) said at the Paris Peace Conference in late 1946 that 9,140 anti-fascist resistance fighters and 20,070 harbourers and supporters had been killed in 1941-1944. In addition to the victims of the “fascist dictatorship” that, according to the Communists, was established after the June 9, 1923 coup, the death toll would thus top 35,000. And yet, data on “those who perished under fascism”, consolidated by order of top party functionary Tsola Dragoicheva in connection with the “People’s Court”, set the total for the 1923-1944 period at 5,134, including 2,320 in 1941-1944. According to the Interior Ministry archives, 1,937 resistance fighters, harbourers and supporters were killed between 1941 and 1944. In confidential documents, the party leadership admitted to the Soviet government that out of 1,590 death sentences for political crimes issued in 1923-1944, only 199 had actually been carried out.

Comparisons with statistics from elsewhere in Europe show that, considering Bulgaria’s small population, its non-involvement in hostilities against the Allies and its refusal to surrender its Jewish population for extermination, this was the most disproportionate post-war retribution in any ex-Axis country.

Understandably, Moscow touted Sofia as a “role model” in this respect to its other satellites. Two films about the Bulgarian “People’s Court” were made, and one of them was requested by the Soviet Union and screened in a number of cities there.

The Statutory Ordinance establishing the “People’s Court” predated by one month the conclusion of the Armistice Agreement with Bulgaria, under which the Bulgarian Government had to “cooperate in the apprehension and trial of persons accused of war crimes”. The Ordinance was adopted while the Soviet Army occupied the country and before the arrival of the British and US members of the Allied Control Commission, who were thus faced with a fait accompli.

Kolarov formulated the underlying idea of property confiscation as “dealing the first economic blow to the bourgeoisie, financing the people’s rule, and assisting the fighters against fascism”. Accordingly, even the assets of deceased persons convicted posthumously were confiscated, including such transferred to spouses and siblings after January 1, 1941. More than 200 enterprises were thus seized, along with a huge amount of immovable and movable property.

Extra-judicial and Quasi-judicial Terror

One of the political tasks of the “People’s Court” was to end, justify and legitimize the biggest single wave of politically motivated killings in modern Bulgarian history that preceded it in September and early October 1944.

While the purge targeted mainly politicians, policemen and military officers, its victims also included teachers, priests, local government officials, engineers, doctors, lawyers, taxmen, forest rangers, writers and students. Researchers estimate that Communist zealots murdered between 8,000 and 30,000 such people without charge and trial. They were registered as “missing persons”, and the authorities turned a blind eye.

US journalist Mark Etheridge, who arrived in Bulgaria in October 1945 as President Truman’s envoy, was told by senior party officials that around 10,000 people had been killed after September 9, 1944. The guest’s own enquiries, however, suggested a far larger figure. He went on record as saying: “Don’t you think that if you keep killing the way you’ve been doing so far we’ll have to send you population from America?”

Collateral Damage

The relatives of “People’s Court” defendants were not spared the purge, either. Nearly 12,000 members of 4,325 convicts’ families were sent into internal exile. For most, forced relocation was ordered even before the court’s hearings began in December 1944.

Party functionaries moved into their homes, and the family members were denied the right to work and to quality education. They were stigmatized for generations as “enemies of the people” and were completely barred from public life.

Party Control

The leadership of the Bulgarian Workers Party (Communist) (BWP (C)) initiated the “People’s Court” project and closely supervised its progress.

In a December 1944 cable from Moscow, party leader Georgi Dimitrov ordered the party decision makers back home: “Nobody must be acquitted!” He was just as blunt in January 1945: “And no considerations of humanity and leniency should play any role whatsoever”.

A draft of the indictment was submitted for approval to a special commission of the BWP Central Committee, and the final version followed Dimitrov’s instructions.

The party’s top body debated the method of execution. Valko Chervenkov (who would succeed Dimitrov and Kolarov as leader in 1949) insisted on public hanging, but BWP Central Committee Secretary Traicho Kostov prevailed, arguing that shooting in private would “do the job quickly and cleanly”.

The court proceedings were monitored by the Politburo and reported to Dimitrov. Kostov personally instructed the public prosecutors not to “measure who is guilty of what” but to “look out for the slightest thing that would prove the guilt of these bandits”. The Communist Politburo discussed and decided the “right verdicts” of the supreme panels, with Dimitrov having the final say.

Judicial and Legislative Review

In April and August 1996, the Supreme Court rendered judgments setting aside the convictions issued by the First and Second Panels of the “People’s Court” and exculpating 175 of the 177 sentenced persons. The court of last resort held that they had been convicted based on a preconceived idea of their collective guilt as members of a government deposed by force, that they were indicted of acts not matching the charged offences and had in effect been punished for their political views and actions.

In a March 1998 decision, the Constitutional Court ruled that “‘the People’s Court’ [had not been] a court existing and operating as part of the regular judiciary” but “an extraordinary tribunal [. . .] whose members [had] even [been] people without legal qualifications” and that that tribunal’s judgments “could not be characterized as judicial decisions”, since they “[had not met] the requirements of due process laid down in the Constitution”.

An Act Declaring the Criminal Nature of the Communist Regime in Bulgaria, passed by Parliament in 2000, listed “the unprecedented liquidation of the Members of the 25th National Assembly and of all innocent people convicted by the co called ‘Peoples' Court’” among the crimes for which the Communist Party leadership and leaders were responsible.

A 2010 amendment to the Political and Civil Rehabilitation of Persecuted Persons Act of 1991 rehabilitated the six Bulgarian members of the 1943 Katyn and Vinnytsia investigation commissions who were convicted by the “People’s Court” Third Panel.

What Historians Say (in chronological order)

Bulgarian and foreign historians remain divided about the People's Court issue:

Prof. Dr Dimitar Tokushev (1982): Bulgaria needed a justice-administering body to establish a new legal order and to satisfy the mass spontaneous and just demand of the people for the punishment of state and war criminals and their aiders. The criminal acts committed by them did not fall within the limits of traditional criminal law. The retroactive action of the Statutory Ordinance on a People's Court was socially justified because, as a revolutionary act, it was directed against the counter-revolutionary forces and sought to punish Bulgarian fascist criminals of various ranks and safeguard the rule of people's democracy.

Joseph Rothschild (1993): The vengeance that the Fatherland Front now wreaked on its political rivals was to be particularly savage, making no distinction between pro-Westerners and pro-Germans. Thousands of old scores were settled, and the proportion of the population executed was higher than in any other former Axis state—despite Bulgaria’s level of participation in Hitler’s war having been the lowest and having entailed the least sacrifices of any Axis partner.

Polya Meshkova and Prof. Dr Dinyu Sharlanov (1994): The People's Court, called a “lawful purge” by its initiators, ended a phase of mass repression unprecedented in our recent history. And the tragic thing is that Bulgarians killed Bulgarians “in the name of the people”. But the guillotine did not stop there. In the following years the opposition parties and their leaders, the proponents of Bulgarian democratic traditions, came under its blow.

Prof. Nikolay Poppetrov (1997): People’s courts were held in a number of countries that were either satellites or occupied by the Third Reich and Italy. The People’s Court can be viewed as an element of the defascization imposed by the time and also by external factors.

Richard J. Crampton (2007): The entire process was political rather than judicial. It was Kostov’s insistence on the most severe of punishments that led to the orgy of judicial killings.

Prof. Dr Georgi Markov (1994, 2014): The enormous number of those sentenced to death gives most historians reason to conclude that the Communist party in Bulgaria, as a Comintern satellite, took advantage of the victorious Great Powers’ decision on a trial of the culprits for the crimes to prepare the country’s Sovietization. In practice, the People's Court was used to liquidate the political, military and some of the intellectual elite of the Kingdom of Bulgaria that might have resisted Sovietization. The “people’s court” verdicts were unprecedented in their cruelty. The illegal confiscations de facto convicted the convicts’ innocent relatives. The purpose of the “people’s court” was neither punishment of the real culprits nor catharsis of Bulgarian society. It was a criminal conspiracy against the Bulgarian nation’s unity and systematic decimation of political opponents.

Prof. Iskra Baeva (2016): This was a common process of punishing the culprits for the crimes. The idea to punish the powerholders in Bulgaria until September 9, 1944 was part of the October 28, 1944 Armistice Agreement. [. . .] These courts, all of them, were illegitimate and irregular with regard to the law.

Assoc. Prof. Mihail Gruev (2016): The Allies, including probably the Soviet occupation authorities, could hardly have imagined a process on such a scale. There is reliable evidence that the Communists’ initial Fatherland Front allies, the non-communist parties themselves, were dismayed by the scale and magnitude of what was happening. The People's Court was conceived as a ‘major spectacle’: the reading of the sentences was broadcast on the radio, the so-called ‘black headscarves’ rallies were organized at the start of the hearing, involving the widows, mothers and daughters of fallen anti-fascists. The trial was meant to imply that no one can be untouchable. The sense of fear it instilled in society proved particularly effective for the Communist Party, which was thus clearing the ground for its complete seizure of power.

Prof. Evelina Kelbecheva (2016): The so-called People's Court was in fact a premeditated and organized, mainly by the communist leaders, mass extermination of the national elite - not only illegal, but also on a monstrous scale. Whatever comparison may be drawn with the verdicts of other post-war tribunals, the victims of the terror in Bulgaria are horrific in their disproportion.

Prof. Dr Nadège Ragaru (2022): Today, few would deny the abundant attacks on notions of independent, impartial, and neutral justice that tarnished the work of the People’s Court, which since 1989 has become a symbol of state violence and “crimes of communism” in Bulgaria. These attacks concern the framework for legal action (the principle of legal non-retroactivity, a lack of recourse to appeal), the drafting of indictments (by a special ad hoc commission at the Party’s Central Committee), the breach of defence rights (conditions of arrest, detention, the obtaining of confessions, access to legal counsel, etc.), and sentencing policy (negotiated between Stalin, Georgi Dimitrov, Traicho Kostov, and Mincho Neychev before the conclusion of the hearings).

Assoc. Prof. Stefan Detchev (2024): The so-called People's Court, founded in September 1944 to adjudicate war guilt, was a parody of legality. The prosecutors were selected on political grounds and the proceedings were choreographed by the communist leaders. The pronounced sentences were politically motivated, excessively severe, and many convicted people were in fact innocent.

Assoc. Prof. Dr Vasilka Tankova (2024): The Statutory Ordinance on a People’s Court is a contra-legal act, the court itself is unconstitutional and its sentences are unlawful and unjust, purely political, aimed at destroying an entire class. A principle unknown to Bulgarian society but known and established in Bolshevik jurisprudence was introduced in the administration of justice: whether an act constitutes a crime or not depends on who committed it. If a person is on a powerholders’ hit list, they are guilty beyond doubt and subject to punishment, possibly execution. Whether or not the person has actually committed a crime is a matter of no particular importance. The Statutory Ordinance criminalized retroactively acts that, when committed, did not constitute offences under the effective legislation. The court panels went even further, inventing offences in the course of the proceedings, like “greater Bulgarian chauvinism”. The undisguised goal of this crackdown was to physically destroy, economically drain and morally discredit the Bulgarian urban and rural bourgeoisie which, in its very nature, is anti-communist. The “People's Court” was nothing but a political crackdown of the Fatherland Front government on hostile (or simply dissenting) individuals and groups. The Bulgarian “People’s Court” did not try war criminals. When US and British politicians and diplomats talk about war criminals, they really mean war criminals, and when their Bulgarian counterparts write about “war criminals” they mean their political opponents.

Media Coverage

Apart from everything else, the “People’s Court” was planned and implemented as a propaganda and PR stunt. The state-controlled media publicized the trials through print, radio broadcasts, newsreels, documentary films and theatrical and musical performances for a target audience both at home and abroad. Special stories appeared daily in the press, with pictures of resistance fighters’ corpses and accounts of the fascist agents’ atrocities.

British, French, and Swedish correspondents were accredited to cover the event, and they can be seen in period photos, bent over their small notebooks, in the front row of the courtroom (and in the second and third row during the busiest times), across from the lawyers’ bench.

On February 5, 1945, Swiss journalist Wolfgang Bretholz approached Tsola Dragoicheva for a takeaway about the sentences and the “urgency” with which they were carried out. The interviewee replied: “Never in my life have I slept better than on the morning of the execution.”

A sample of coverage in the foreign press:

The Times of London (February 3, 1945): By this all-out purge of the oppositionists, the regime intends to do away with all other parties.

Efimeris ton Valkanion, Thessaloniki (February 5, 1945): Political blame and political expediency are mainly to blame for these executions. By them the present-day factors in Sofia are pursuing the liquidation of a policy line which those executed adopted or pursued and which led the country to war and catastrophe. But this policy was for decades the national policy of Bulgaria and focused the thoughts and actions of all politicians and of all Bulgarians both in peacetime and during the European war. This national policy was followed by the Bulgarians with few, very few exceptions. Those executed were patriots from the Bulgarian point of view and applied a policy which all Bulgarians thought led to the implementation of the national ideals. These politicians were applauded until a few days ago by the entire Bulgarian people. Their execution is a political crime and is no different from the war crimes that will be punished in the near future.

Tanin, Istanbul: Bulgarian justice surpassed the cruelties and inhumanity ascribed to Huns and Asians.

BTA’s Share

The Press and Propaganda Department of the Ministry of Propaganda (the predecessor of today’s BTA) had an important part in reporting and commenting on the “People’s Court” developments. Following are excerpts from an item in the Dnevni Vesti [Daily News] bulletin, covering the February 1, 1945 hearing at which the First Supreme Panel of the People’s Court pronounced the sentences against the top people in the old regime:

“At 3:30 p.m. the defendants were ushered into the courtroom with an escort of militsiya officers, all of them former resistance fighters. The defendants were lined up: the three regents and Filov's first cabinet, Filov's second cabinet, Dobri Bozhilov's cabinet and Bagryanov's cabinet and Muraviev's cabinet. [. . .]

Panel President Bogdan Shulev declared the hearing open and entrusted Vice President St. [Stefan] Manov with reading the sentence.

The defendants, who until that point had been talking among themselves, stood up, their faces pale, their jaws clenched tightly, as Vice President St. Manov read the sentence in dead silence. The defendants paled with every passing moment and after every word that placed them in the verdict of the people. They listened, and it was clear from the expression on their deathly pale faces that many of them did not understand the clearly and curtly articulated words of the sentence. [. . .]

Manov read the People's Court sentence, and as his voice grew firmer, his face tightened and his eyes, which had wept so much sorrow for a lost son who fell victim to those whose sentence he was reading, focused on the words of the sentence. This is not a personal verdict, this is not a verdict of one man against another, this is a verdict against a system.”

On February 2, 1945, the Information Bulletin of the Press and Propaganda Department carried full English translations of the sentences of the People’s Court First and Second Supreme Panels.

Here is the original unedited version of a report in the same bulletin about a rally held on the previous day after the delivery of the sentences:

“Sofia, Febr. 2, 1945

The region committees of the Fatherland Front, in connection with the sentences which the supreme Staffs of the People’s Tribunal, announced yesterday at 4.p.m. orginised [sic] a great meeting of Sofia citizens, before the court of justice. The people gathered in the name of the whole Bulgarian nation, to hear the sentences, passed by the People's tribunal on the ex-Regents, court advisers and deputies from the XXV national assembly.

More than 200000 citizens poured into the square of St. Nedelia and the streets around the court of justice. All of the F.F. [Fatherland Front] organisations together with their banners and placards were present not only to hear the sentences passed, but to express their will for the immediate execution of the sentences, according to the law. Before the central door of the court of justice is built a small estrada [platform], near which are the officials, generals, representatives of the national committee and the region Fatherland Front committee, and representatives of the political organisations. The president of the Fatherland committee Mr. Lulcho Chervenkov [Valko Chervenkov’s brother] opened the meeting with a short speech. After that the representatives of all political organisations forming the F.F. delivered short speeches.

Dr. Luben Gerasimov spoke on behalf of the worker’s party /communists/.

The member of the region F.F. committee, Mliaskov [sic, must be Mlachkov], delivered a speech as a representative of the Bulgarian National Agrarian Union.

In the name of the People’s Union Zveno spoke Mr. Trifon Trifonov and at the aend [end] the president of the region committee Mr. L. Chervenkov, read the following resolution:

“Today 1 of February 1945, the great meeting of Sofia citizens, hearing the sentences passed and the speeches of the orators, decided that:

- Approves the sentences passed by the judges of the People’s Tribunal and congratulates them, since they fulfill the will of the Bulgarian nation for a severe and merciless sentence passed upon the traitors of the Bulgarian national interests. The passed just sentence, proving that the people never did approve the treacherous and criminal policy of the fascist servants in Bulgaria and that all guilty for the war declared on England, U.S.A. and the brotherly Soviet Union will also receive a merciless punishment.

- We wish that the sentences should be immediately executed.

- We wish that all traitors and executors will be discovered and most severy [sic] punished. A quick purge of all Fascist elements from the state machine.

Death to Fascism.”

/LG/

Additional

news.modal.image.header

news.modal.image.text

news.modal.download.header

news.modal.download.text

news.modal.header

news.modal.text